Presence and Absence and Substack

Andrew describes why he is starting a Substack

My good friend’s former campaign manager told me I should start a Substack.

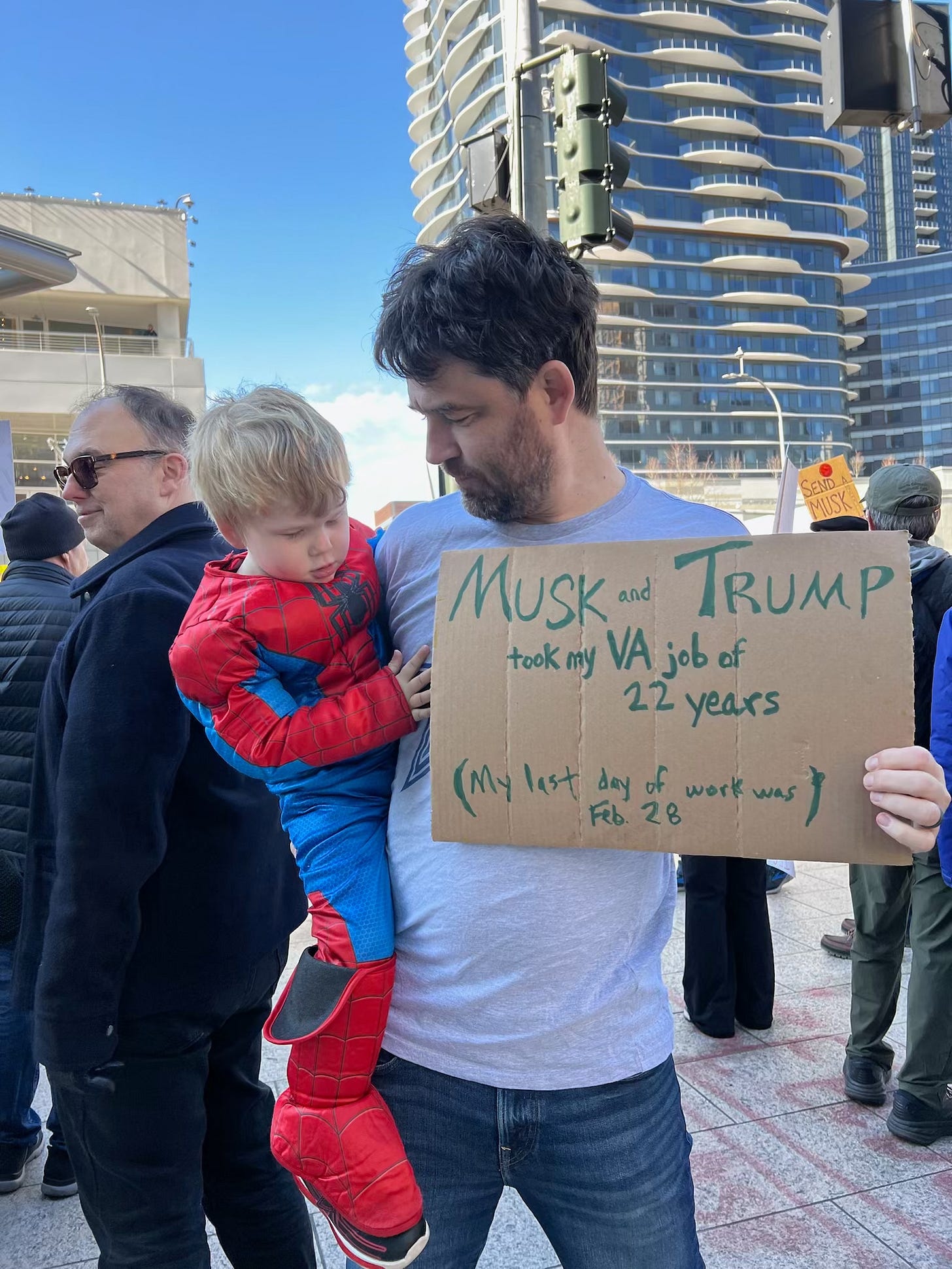

Then, in President Trump’s quest to put American workers on unemployment and dismantle research, he eliminated my job with one of his dime-store executive orders. Suddenly I was free to do fun things, like draft résumés and cover letters, apply for utility subsidies, and, yes, create a Substack.

* * *

Awhile back, I drafted an essay about my body and my relationship to that body.

In that essay, I described how I’d been lucky enough to edit an issue of The Other Journal that focused on bodies—on big bodies and broken bodies, on miscarriages and incarceration rates, on racial stereotypes and the many ways our culture exalts and shuns the feminine body. Then, I noted in my essay how my body was absent from those pages. “My thin arms, middle-aged knees, and pale skin never made a cameo there,” I said.

I considered how that kind of absence was a feature of life for many Americans, particularly those of you who are not white, male, and straight. “There are lessons in the things we make absent,” I wrote. “Meaning gathers in the shadow of the unsaid, in the rumpus of the things we hide away.”

That has me thinking now of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the man who was sent to a US-financed prison in El Salvador because of what our government’s lawyers described as an administrative error.

* * *

It may be a bit silly to be quoting myself, but I want to linger here on the implicit question that my essay tried to ask—who am I, a white, straight male, to claim space?

Who am I to seek your time and attention?

I haven’t had my story disappeared because of my familial history or personal attributes. You don’t owe it to me to tune in.

I’m not famous, culturally hip, or a reliable source for breaking news or crunched statistics.

I can’t recite Plato or Tupac, and my primary expertise—reading, writing, and editing—isn’t novel.

But perhaps I can find ways to take things that are absent and make them visible; perhaps there is power and beauty in the simple revelation of an ordinary life.

* * *

I am here to write from my particularity into your particularity, to share my story and the lessons I am learning from the everyday, from headlines and fictional characters and my kids.

I’m here to write openly about what it means to be me—what it means to be a husband, to be the father of young children and estranged teens, to be a progressive and a Protestant in the era of Trump.

I am here because I believe in love and beauty and twilight truths and because I want to do my part to celebrate presence.

I hope you will join me.